Threat Hunting in 2024: Must-Have Resources & Tasks for Every Hunter

Imagine it’s your first day at a new organization and you’re asked to develop a plan for threat hunting. To plan effectively, you must investigate questions such as:

- What are the top tasks that threat hunters perform every day?

- What are the most important resources at their disposal?

- How can you streamline these tasks and resources into a repeatable process to guide the team?

The SURGe team of security experts wanted the answers to these questions, too, since streamlining operations is key to an effective threat hunting program.

That’s why we surveyed and interviewed working threat hunters: by understanding the most important activities, resources, and processes that threat hunters use every day, teams can create repeatable workflows that help identify and mitigate threats.

So, who took the survey? Here are some quick facts about our 61 respondents:

- Nearly half (46%) work at organizations with 10,000+ employees and threat hunting teams with 1-3 members.

- A majority (59%) have 1-5 years of experience in threat hunting.

- Another 26% have 5-10 years of experience in this field.

Essential Threat Hunting Tasks

To start, we asked these threat hunters about their most essential tasks.

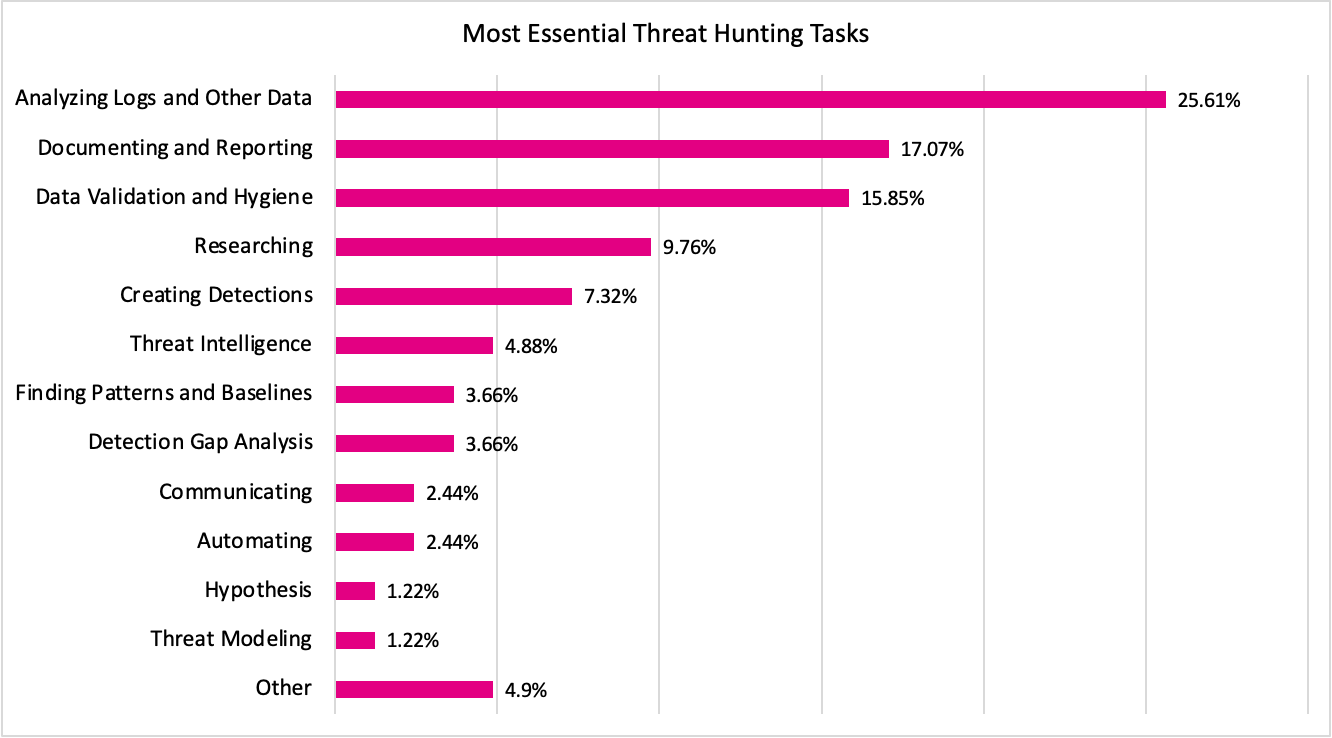

Figure 1: Most Essential Threat Hunting Tasks

Data analysis, validation & hygiene

Two of the top five essential tasks encompass data. As shown in Figure 1, we see:

- Data analysis ranked highest (25.6%), which is no surprise since this task is at the heart of threat hunting.

- Validation and hygiene — e.g., “cleaning” the data to make sure it’s correct, consistent, and in a state to be easily analyzed — came in third (15.9%).

Most data scientists would consider these tasks to be two halves of the same whole; taken together, they blow all of the other responses out of the water (41.5%).

For teams that align their operations with the PEAK threat hunting framework, these two actions fall solidly inside the Execute phase of the hunt.

Documentation & reporting

Coming in second on this list is documentation and reporting. This placement also makes sense because our hunts have the biggest impact only when we can:

- Write down how we did and what we found.

- Then share that information with other stakeholders.

In PEAK, these activities fall under the Act phase, and are key to generating the Knowledge that is not only crucial to good security decision-making, but also informs subsequent hunts.

Research

Next on the list is research (9.8%). This is slightly surprising, not because it’s on the list, but because of its position. Most hunts begin with researching a topic or tactic (it’s part of PEAK’s first phase, Prepare); jumping directly to data analysis is usually not recommended.

For this essential step to be ranked so low implies that many threat hunters may be skimping on the research, or even skipping it entirely.

Detection creation

Rounding out the top five is detection creation, another part of PEAK’s Act phase. While the hunt team may not always develop detections themselves, detections are one of the most common outputs of a hunt. One respondent put it this way:

“You call out detections as part of hunting, which it is, but it's become [a] separate discipline as well. I'll be curious to see how respondents select between those, as we've essentially split detection engineering into [a dedicated team].”

Essential Threat Hunting Resources

With our survey, we also wanted to find out what tools and resources threat hunters felt were the most essential.

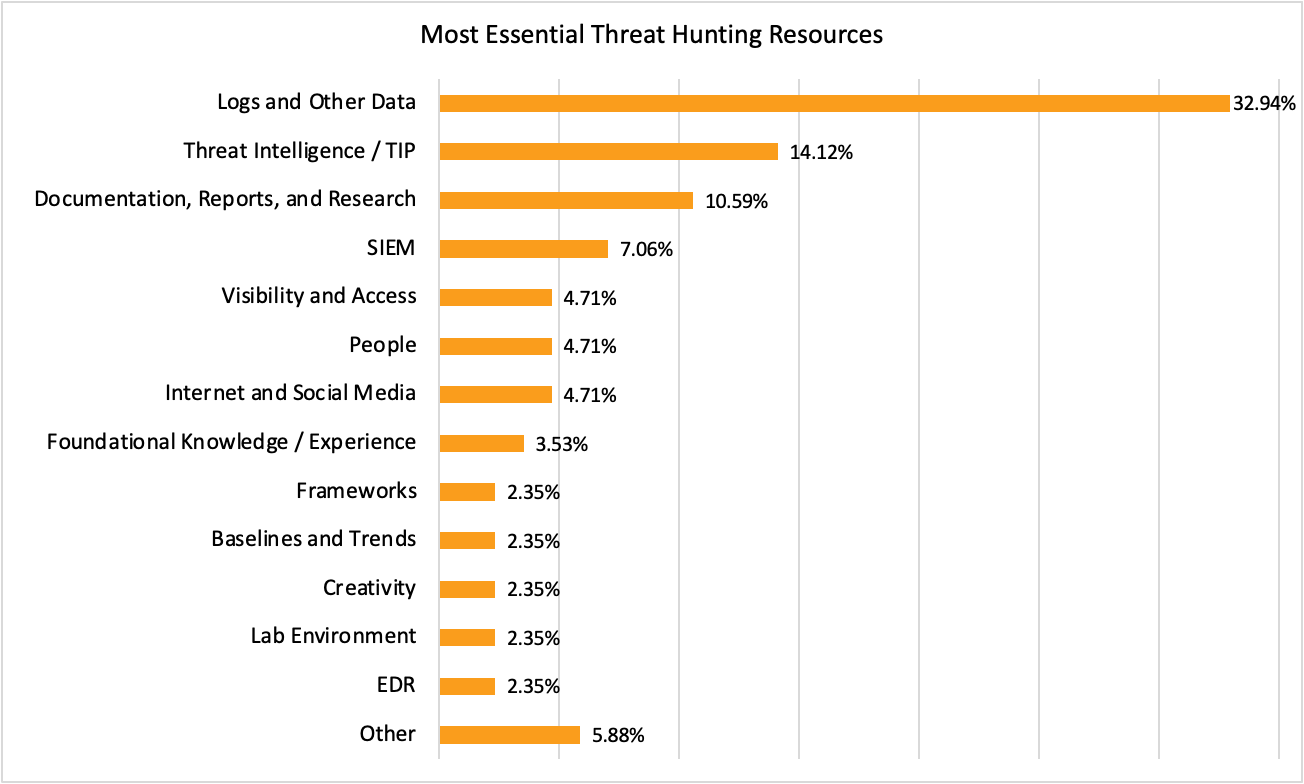

Figure 2: Most Essential Threat Hunting Resources

Logs & other data

Logs and other data was ranked the most important resource by nearly a third of respondents (32.9%). Again, this is unsurprising given the nature of threat hunting, and we know that logs and other data are resource #1 for hunting.

The next two answers are perhaps more interesting.

Threat intelligence

Our respondents ranked threat intelligence as their second most essential resource. This implies that most threat hunts are informed, if not actually driven, by real-world knowledge of threat actors and their activities.

Although we did not specifically ask about it, this result is compatible with MITRE Engenuity’s concept of Threat-Informed Defense, which is good news for the cybersecurity community at large.

Documentation, reports & research

The next most essential resource was Documentation, Reports, and Research, a category that includes such items as:

- Gap analyses or other hunting recommendations from various internal sources.

- Custom dashboards or alerts from detection rules that aren’t quite reliable enough to send directly to the SOC (some organizations refer to these as “hunting alerts”).

Taken together, these serve as a complement to threat intelligence, sometimes referred to as friendly intelligence. This supports the idea that knowing your adversary is not enough — for the best security outcomes, you also need a detailed understanding of your own environment.

Daily tasks for threat hunting

The beginning of a workflow often provides momentum for later tasks. Though we recognize that threat hunting is, by nature, flexible and may not have a well-defined daily structure, we were interested in what the first task would likely be.

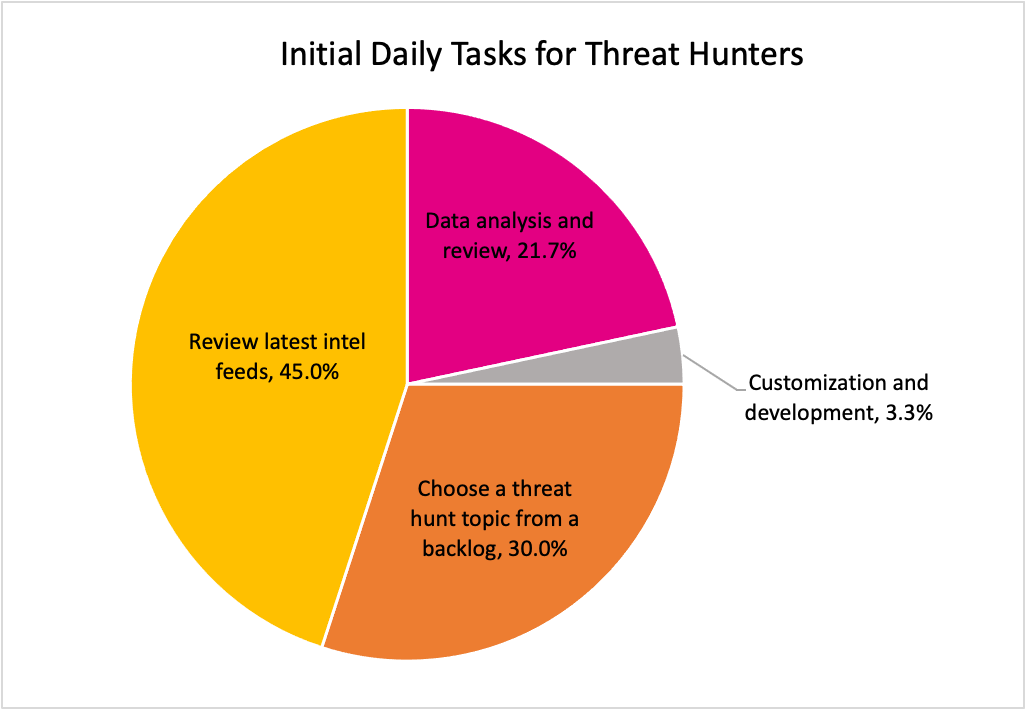

Figure 3: Initial Daily Task for Threat Hunters

Almost half of respondents (45%) indicated that most days, their first hunting-related task is to review external sources such as:

- Blogs

- Intel reports

- News articles

This aligns with results from the 2024 SANS Threat Hunting Survey, in which well over half of respondents indicated that they leverage similar external sources to keep up-to-date on the latest threats. Although the SANS survey did not specifically ask about when respondents did this review, doing this as the first (or one of the first) tasks of the day makes the most sense from a workflow standpoint.

Collaboration methods

Information sharing is a critical part of any hunt, both within the hunt team and with non-hunters who have some interest in the process (for example, system owners, or those who provide data to the team).

Collaborating during the hunt

In our survey, we asked about the most common methods for collaboration with stakeholders during the hunt.

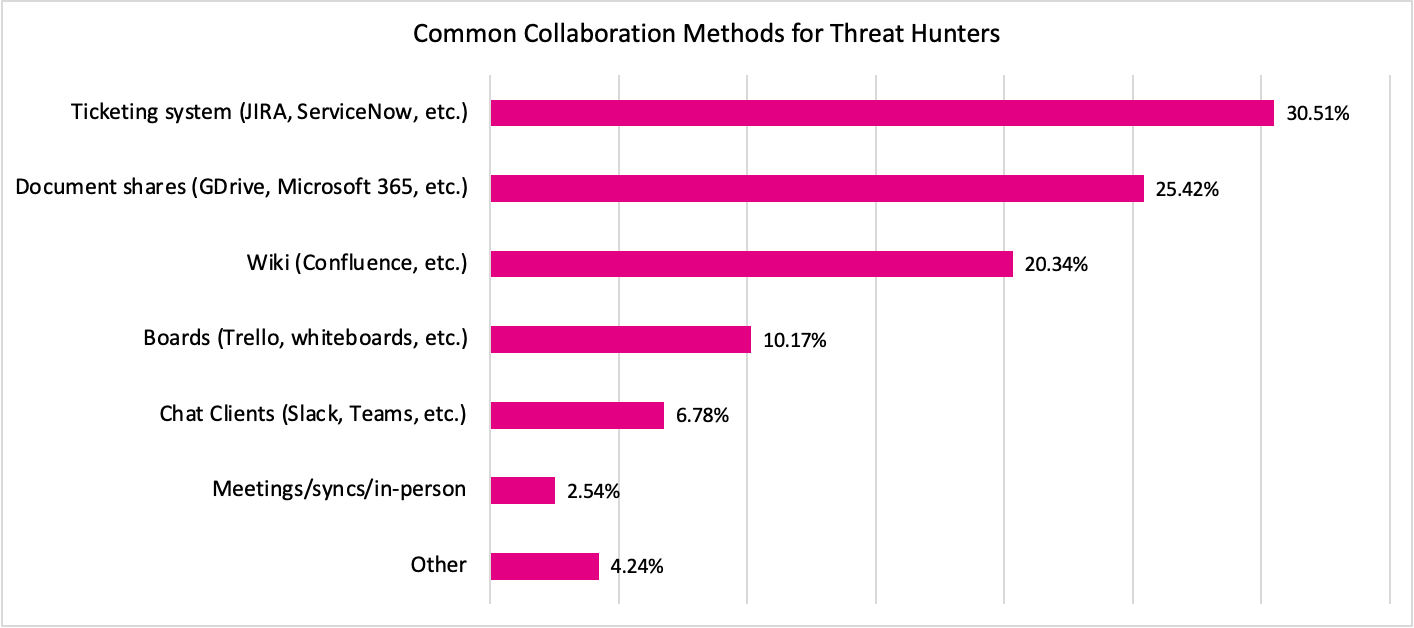

Figure 4: Common Collaboration Methods for Threat Hunters

Figure 4 shows that many respondents (30.5%) indicated that some form of ticketing system is their primary method of collaboration with other team members. This makes sense as ticketing systems make it easy to assign tasks and follow workstreams attached to tickets.

The second highest ranked method was Document shares (25.4%), with wiki platforms coming in third (20.3%). In fact, it seems as though these are often utilized as a set; many of our respondents (42.6%) indicated that they use some combination of two or three of these mechanisms.

Post-hunt collaboration

Collaboration is just as important after the hunt as it is during, and the most common form of post-hunt collaboration is hunt documentation — that is, recording what you did, why you did it, and what you found.

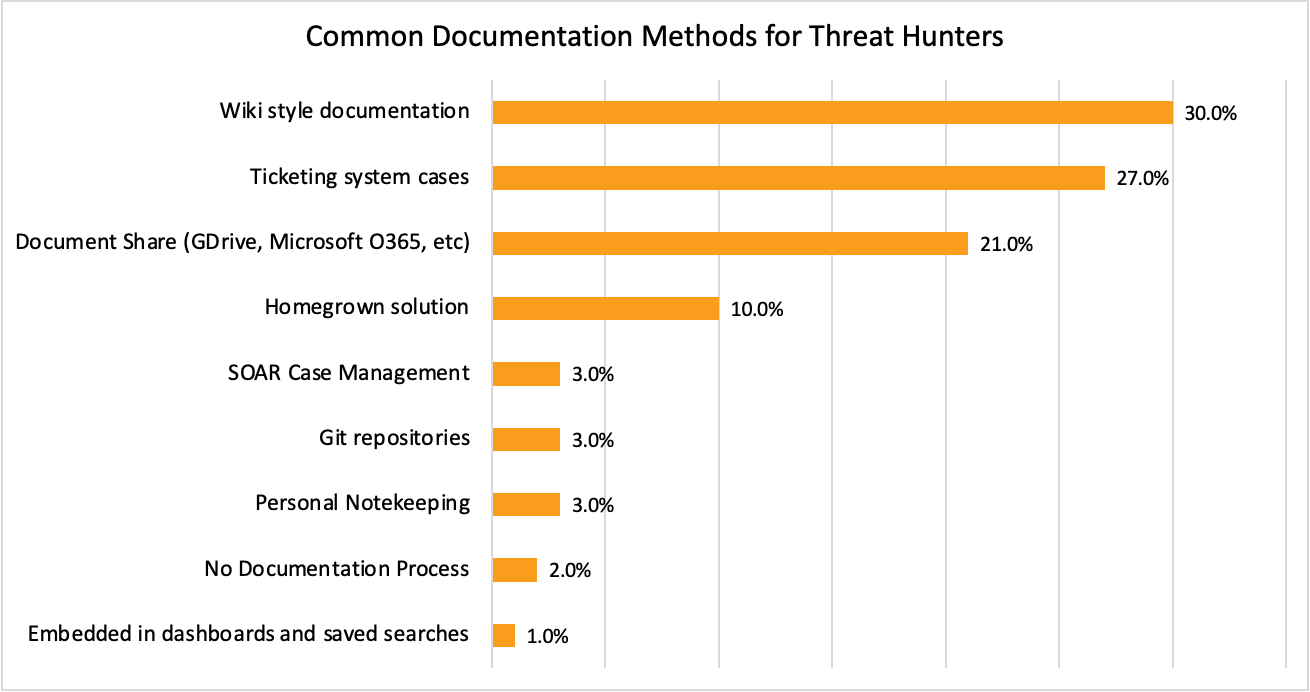

Figure 5: Common Documentation Methods for Threat Hunters

In Figure 5, we see that respondents indicated their most common platforms for post-hunt documentation:

- A wiki (30%)

- Ticketing systems (27%)

- Document shares (21%)

Interestingly, these were also the top collaboration tools used during the hunt, though in a slightly different order. Wikis come out on top in post-hunt collaboration but are only ranked third during the hunt. This probably reflects the tendency for documentation to be expressed in long-form text rather than task-based updates, and because the longer articles stored in wikis can’t be written until the hunt is finished (or nearly so).

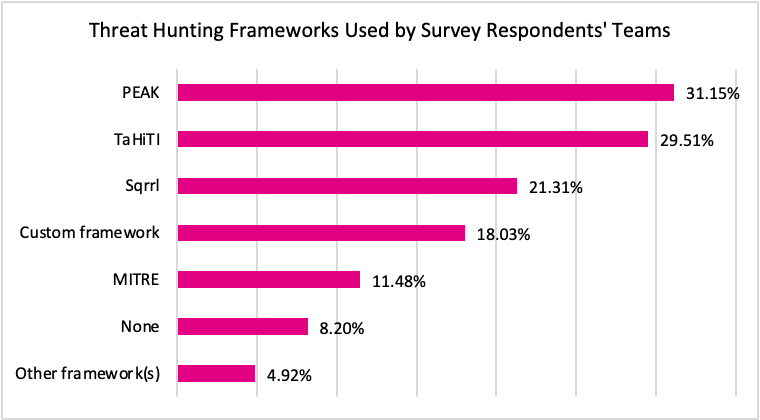

Streamlining threat hunting processes

Creating or adopting a well-defined framework for threat hunting is important to help streamline your process. This is underscored by the fact that the vast majority of our respondents (77.0%) followed one or more of the published threat hunting frameworks (e.g., Sqrrl, TaHiTi, PEAK) or developed their own.

Figure 6: Threat Hunting Frameworks Used by Survey Respondents’ Teams

Summary of key findings

The results of our survey show that data is king. Analysis, validation, and hygiene are not just everyday tasks — this tasks are the heart and soul of threat hunting. Even so, research may not be getting the attention it deserves. As one of the central activities in hunt planning, organizations would do well to emphasize the importance of research when prepping a hunt.

It's also clear that threat hunting doesn't happen in a vacuum. Threat intelligence and internal documentation are the two largest parts of PEAK’s Knowledge component for good reason: they are the foundation of a threat-informed defense that's grounded in a deep understanding of one's own environment. Collaboration, both during and after the hunt, is also crucial to success, with ticketing systems, document shares, and wikis emerging as the tools of choice.

Perhaps most importantly, our survey highlights the value of structure and process. The widespread adoption of threat hunting frameworks, whether off-the-shelf (e.g., PEAK, Sqrrl, or TaHiTi), custom-built, or a combination of these, shows that organizations are actively looking for repeatable processes and trusted standards in this area.

Roadmap for threat hunting

For those embarking on the threat hunting journey, these insights offer a roadmap:

- Focus on your data.

- Leverage intelligence.

- Collaborate widely.

- Document thoroughly.

- Adopt a structured methodology.

For seasoned hunters, these responses provide a benchmark to assess and refine your operations.

The threat landscape is vast and ever-changing, but with the right tools, resources, and processes, organizations can leverage their threat hunting programs to pay big security dividends.

Share responsibilities

Despite all the work you've put into your hunt, there are some times where the execution or action on a threat hunt is not fully conducted by the threat hunter. Do not be afraid to share responsibilities.

Successful threat hunting really is a team sport. We know that it can be challenging to take a hunt activity that has been in flight for a long time and pass it off to another team to make content that comes as a direct result of the work; however, we encourage you to collaborate and share responsibilities with other teams where appropriate.

In fact, that's exactly what this article, Splunk Tools & Analytics To Empower Threat Hunters, does. In that article, Mauricio Velazco, a member of the Splunk Threat Research Team, discusses how his team both:

- Uses these exact same tasks and resources, despite having a different goal from threat hunting.

- Leverages concepts from the PEAK framework for developing detections to execute on a threat hunt.

By learning from the collective experience of the hunting community, as reflected in these survey results, we can continue to hone our craft and keep our organizations safe. Happy hunting!

As always, security at Splunk is a family business. Credit to authors and collaborators: David Bianco, James Hodgkinson, Shannon Davis, Audra Streeman, and the many other SURGe team members and Splunkers who contributed to editing, data review, and many other aspects of this project.

Related Articles

About Splunk

The world’s leading organizations rely on Splunk, a Cisco company, to continuously strengthen digital resilience with our unified security and observability platform, powered by industry-leading AI.

Our customers trust Splunk’s award-winning security and observability solutions to secure and improve the reliability of their complex digital environments, at any scale.